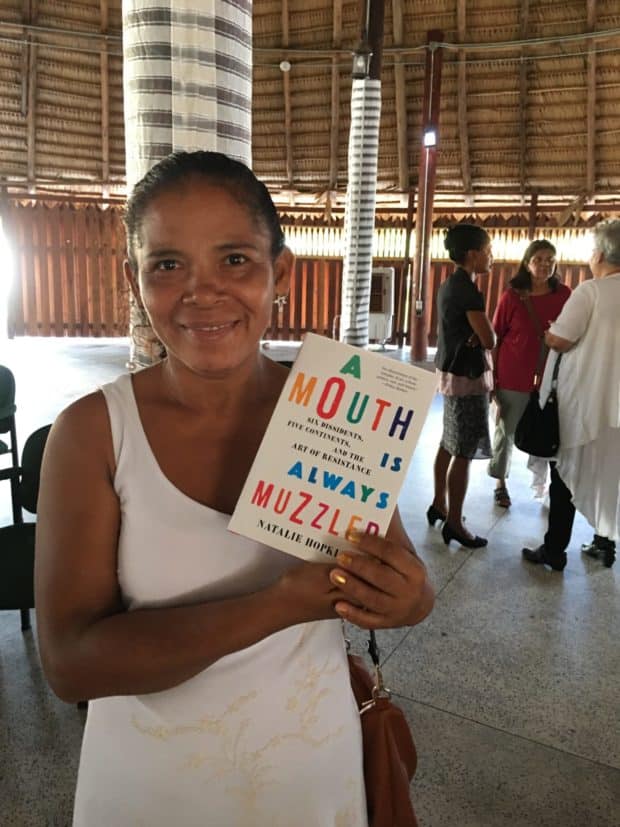

IF Fellow Dr. Natalie Hopkinson was invited to deliver the Republic Lecture by the government of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana on Feb. 22, 2018 on the role of the creative arts in citizenship. She was also invited to launch her new book, “A Mouth is Always Muzzled: Six Dissidents, Five Continents and the Art of Resistance” on the The New Press, which has won favorable reviews from NPR, Kirkus magazine, Publisher’s Weekly, Forward magazine and is mostly set in the author’s family’s native Guyana.

Both the book and the speech was an outgrowth of the Interactivity Foundation’s Future of the Arts & Society project.

Bernice Benn was one of the local audience members that attended the lecture. It took place at Umana Yana, a conical palm-thatched hut built by the Wai-Wai Amerindians, one of the nine indigenous tribes of Guyana.

Below is the text and slideshow images from the speech:

Greetings from Washington, D.C. Thank you to President Granger, Prime Minister Nagamootoo and the Honorable Ministers Joseph Harmon, Dr. George Norton and Nicolette Henry for your leadership, and hosting me here to deliver this Republic Lecture on the occasion of celebrating Guyana’s establishment as a Co-operative Republic.

It is the honor of my life to be here and speak to you. I come from very humble beginnings. My late father, Terrence Hopkinson, grew up here in Georgetown in the neighborhood of Lodge, the son of a seamstress and a police officer. My dad attended Queen’s College, where IBM recruited him in the 1960s. My mother was born Serena Baird, and hails from the Pomeroon River off the Essequibo Coast. Her family raised mangos, rice, provisions, eddoes, coconuts. They sold them at Stabroek Market where the matriarch of the family, Mother Benn had a stall.

Each morning, my mother and her eight siblings paddled by boat to Marlborough R.C. school. My mother and two of them are here today: My Auntie Lynette George and Uncle Calvin Benn. There was no electricity, but at the time, they did not notice. They learned math, English, geography. My mother loved to read books. In her mind, she traveled to new dimensions on earth and beyond.

My mother never once considered herself “poor”. She also did not know of a word like “art” or imagine that one day it would bring her here today with me for this great honor. Art was not something they talked about in school. Art was never connected with her aspirations. Dreams were for banking, medicine, law—computer engineering. What is art anyway?

This is the question I have been asked to address today. What is art? What are the roles of art in society? What does art have to do with exercising citizenship in a cooperative republic? I will add another question: How can art help us imagine a radical future?

This month, my latest book, set in Guyana, has been released. It is called A Mouth is Always Muzzled after the famous Martin Carter poem. At the beginning of this journey of writing this book, I began doing a series of discussions with people about the role of the arts and society on behalf of the Interactivity Foundation in 2011. I facilitated discussions all around the U.S. and the world, including here in Georgetown at the Night Cap cafe. I vividly remember one such panel we held in Miami, Florida. A woman said: Isn’t it irresponsible for us to teach our underprivileged youth a subject like art in schools, when they have no realistic chance of making a living at it. Isn’t that a poor use of their time, and cruel?

This broke my heart. But I must admit, that this is the prevailing view.

When it is addressed at all, this is the notion of art that is foisted upon brown and black people all around the world. It reflects a profoundly limited understanding of the range of possibilities of what art is, and what art can be. It also reflects a kind of global disorder. This is the sickness that we automatically calibrate every human endeavor to the gears of capitalism. It is a bankruptcy of the imagination—a poverty of the human spirit. Material poverty is a real thing, but it can be overcome. When spiritual poverty takes root in a society, there is no hope left, no reason to continue bring more people into this world.

Art is about radical imagination. It is about imagining a future we cannot now see. It is about refining our individual expression as humans. It is not only for the poets and the painters; It is also for the woman and man on the street. We are in trying times. We need all hands on deck. No voice or vision can be left behind.

Back in the U.S., we are in the midst of Black Panther fever. This an Afrofuturistic film about the fictional country of Wakanda, the wealthiest and most technologically advanced country on the planet located somewhere on the African continent. But the world thinks they are just another “third world” country. They hide their wealth, natural resources, technology and power in the mountains and impenetrable rainforests. This is true science fiction. In this alternate future, they say El Dorado city of gold was not here in Guyana, but it was actually there in Wakanda!

The film stars another daughter of Guyana, the brilliant actress Letitia Wright who was amazing in the Netflix sci-fi series “Black Mirror.” The film is visually stunning. The Wakandan landscapes blending rainforests and high-tech transportation and traditional villages could easily be here in Guyana. Looking at one dreamy sequence in which the King confers with the ancestors while black panthers look on, the cinematography brought to mind the work of Khadijah Benn, a photographer and cartographer who lives and works here in Guyana. My dear friend, the curator Grace Aneiza Ali whom I understand was also here this month, introduced me to Khadijah’s work years ago in London, and it continues to exhibit all over the world.

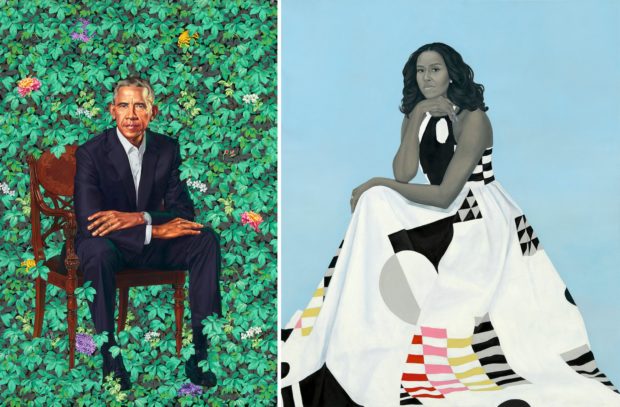

Black Panther is part of a genre called “Afrofuturism.” It is partly science fiction, but also includes black culture and history. Some people call it Afropunk. Some examples are the works of writers Nalo Hopkinson, Octavia Butler, and the funk group Parliament Funkadelic and singers Janelle Monae and Missy Elliot. You may have seen the official White House portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama by the artists Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherman. They have a bold color palette and visual style like no other President and First Lady in American history. These images float above this earthly world. They are for the future.

Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald’s official portraits of President Barack and First Lady Michelle Obama.

I heard the Black Panther director Ryan Coogler give a talk in Washington, D.C. He said at screenings around the world, audiences arrived wearing traditional Mexican, traditional Singapore, and traditional African garb. To have the most maligned continent be a such an inspirational force, uniting all of the colored peoples of the world, is a beautiful thing. It can be considered part a movement some in the art world are calling “ethnofuturism.” It starts at the root, Africa, from whence we all came. But it spreads out to the colored world. It is magnificent.

I was at yet another Black Panther screening last week in Washington, and a prominent activist in the Black Lives Matter movement talked about this idea of radical imagination and afrofuturism. The question was how can it help us to unlock the potential in struggling black and brown communities around the world. Philip Agnew, who is head of the powerful organization or young activists called the Dream Defenders, said the radical potential of art is about imagining brand new paradigms for how we order society. To him, Afrofuturism is not just about replicating and flipping the patterns of history, with one race ruling another. It is about imagining brand new ways to organize the social contract beyond the constructs of capitalism and race. It’s about developing “cooperative” societies. And he uses this phrase, “cooperative” society. He said he has been disappointed that as imaginative as young people can be, so many of them struggle to imagine a world without capitalism.

I spoke to Phil after his speech and I told him: Hey Guyana is nearly 50 years ahead of you! That is what we are celebrating here in Guyana this week, Mashramani and the celebration of Guyana’s establishment as a Co-operative Republic in 1970. Art was an integral part of Guyana’s notion of independence. The poet A.J. Seymour explained: “For the artists of Guyana, the revelation of a national identity is the most revolutionary possibility that exists…The Guyana man has to re-create himself in his own image as an indispensable basis on which to realize the image of a national identity.”

I open my book here at Mashramani, the Republic celebrations in the first chapter. Mashramani can be viewed as an early prototype for ethnofuturism. In that spirit, I want to suggest that Mashramani is a cultural phenomenon that brings us message from both the past and messages from the globalized future.

Guyana’s Mashramani festival puts indigenous cultural identity at the center of their national celebration.

Some back story: Long before Independence, Guyana’s major leaders tied art to resistance and connected it to the notion of a cooperative society. Janet Jagan protested colonial authorities who banned “Revolt” a 1960 painting by Aubrey Williams that depicted an escaped slave ravaging a white plantation mistress. As a young lawyer under British rule, Forbes Burnham challenged colonial-era laws that cracked down on street musicians and African traditions such traditions such as ‘obeah.’

In 1970, Guyana declared itself a “Co-operative Republic” which was an early experiment in socialism. Coming at the height of the Cold War, this declaration was bold. It greatly angered the Western imperialists who thought they had defeated this revolutionary spirit when they muzzled Cheddi and Janet Jagan. Shocked by this cooperative turn of events, the U.S. cut off all economic aid. They spent $18 million on Guyana in 1968; By 1974, that number was cut to $200,000.

When Guyana became a “Cooperative Republic” it rode a wave of radical politics that was catching fire throughout Latin America. Guyana’s notion of cooperative was based on sharing economic societies in India and Africa, and it was one of the first experiments like it in the world. This radical ideology applied to the cultural realm as well. A series of monuments were erected in this vein, from Enmore Martyrs, Phillip Moore’s Cuffy “1763” statue, and of course, Umana Yana, the traditional Amerindian building built by Guyana’s first peoples where we are gathering today. The first Carifesta was hosted here in Georgetown and the annual Mashramani festival began. All were launched in the 1970s as part of this cultural liberation movement.

Famed sculptor Philip Moore created this “1763” monument to commemorate the rebellion on Feb. 23, 1763 of an enslaved man named “Cuffy” who led a rebellion on sugar plantations and ruled the Dutch colony of Berbice for nearly a year.

Mashramani builds on many carnival traditions all over the world. The scholar Kevin Adonis Browne’s theory of “mas rhetorica” can be a way to think about all of these celebrations. He argues that carnival is a language, a way of seeing, a way of being seen, and of being. The Russian philosopher Bakhtin noted that in Medieval Europe, carnival was all about collapsing the wall between actor and spectator. To our neighbors in Trinidad, Haiti, and in New Orleans, where my husband grew up, carnival performance traditions ritually mock the ruling class. Back on the East Coast of the U.S., West Indian Labor Day festival in Brooklyn is a conversation about the history of work, migration and pan-African solidarity.

Mashramani is part of a tradition, but in some ways, stands alone. It is named after an Arawak phrase for a celebration after cooperative hard work, and it puts this indigenous history at the spiritual center. Few other West Indian societies have such a large indigenous population that survived genocide as Guyana. Even fewer put indigenous tradition at the very center of how they understand themselves as a nation. Even this boldness of simply declaring itself Guyana, land of many waters, is a statement against imperialism. Guyana reclaimed itself before the intervention of the Europeans and declared itself a “co-operative” society on top of that.

Guyana has a long path to Wakanda. As the process of emancipation continues, these ethnic, economic and historic divisions will always ring loud. Liberation is a process. But through repetition, through sharing our competing and clashing voices, we can construct an entirely new world, a new reality. All the descendants of all six of Guyana’s peoples are represented in music, food, dance on the floats and on the sidelines in the Republic festivities. As all the people participate in Mashramani this week, even if it is to complain, are all part of weaving this beautiful tapestry, this vision of the future.

The other characters in my book can be viewed from an ethnofuturistic lens. There is first the fabulous Guyanese painter and critic Bernadette Persaud, whom I am looking forward to visiting with this week. Her lush topographies project the magical beauty of Guyana’s landscapes, juxtaposed with the ugliness of power and brute force. Her work is in conversation with Hindu mythology and asks questions about the infinite realm that we cannot see.

Ruel Johnson contributes to this conversation through his prize-winning poetry and short stories. Like one of his influences, Negritude poet Aimee Cesaire before him, he has taken his talents to the public sector. For years, he has been seeing visions that once sounded like pure science fiction. The idea that the art and the creative sectors are the tools for Guyana to win the economies of the future. But now with the oil money, I see how it may be possible. In my own imagination, I see Ruel hard at work, using his well-known, let’s call it, tenacity, to badger Marvel to come to the real El Dorado here in Guyana to film the next Black Panther! Tell them it’s Guyana that has the real panthers, too, Ruel!

Another of my book’s chapters that could be considered ethnofuturistic is Sweet Ruins. I feature the American artist Kara Walker, who erected a massive Sugar Sphinx sculpture installation an old Domino factory in Brooklyn, New York in 2014. Her Sugar Sphinx sculpture, made of 40 tons of sugar, and the social media campaign around it, created an interactive monument to black and brown womanhood and its living legacy of exploitation. I put her work in conversation with the writer Gaiutra Bahadur, who wrote Coolie Woman about Indian indentured women sugar workers in Guyana.

Time travel is an important element of ethnofuturism. To explore the past, I also travelled to London for the story the white British novelist John Berger. Berger was awarded the Booker prize in 1972. He gave a fiery acceptance speech calling out the Booker sugar and rum company for exploiting Guyana for 150 years. He also gave half his prize money to the Black Panther Party. There’s that black panther again.

The final historical detour in my book reexamines the spectacular life and legacy of the great Guyanese historian Walter Rodney who needs no introduction here. I was in Jamaica last month and met Dr. Matthew Smith, chair of the history department at the University of the West Indies. He just finished a new film about Rodney’s life that premiered last week in Kingston. He told me Rodney is their department’s most famous graduate. He hopes Rodney’s life inspires a new generation of scholars at the University of the West Indies.

Lastly, I want to share a note on the book’s title: This was a stanza in a poem by the great Guyanese poet Martin Carter, whose story I also tell in the book. It reads:

“A mouth is always muzzled/ by the food it eats to live.”

Martin Carter’s poem, “A Mouth is Always Muzzled,” expressed an essential truth about the human condition.

This is an essential truth that could fill endless more books. All around the world, all of our mouths are muzzled. Every last one of them. I believe Trump’s mouth is muzzled. Perhaps not enough, but still. Unless you are starving to death, you are making compromises. In a small country like Guyana, that struggle and those compromises are very vivid.

So, I would like to thank the people of Guyana and her Diaspora for allowing me to write this message from the future and to speak to you about it today. If I may offer one suggestion to Guyana and the world at large, it is to resist these forces that say art is of no consequence.

Art is what makes life worth living. It enriches our humanity. It is also our collective responsibility as global citizens. Each one of us has a duty to be involved in writing the histories of tomorrow and the futures of today. I have written one chapter of Guyana’s contemporary art, politics, and history. But that is just one story, one version of events. The world also needs to hear yours. Whether it is film, books, YouTube, selfies, paintings, music, dance, Tweets—embrace what you feel inside—and keep sharing it. Last year, when I was here for my grandmother’s funeral, my mother, daughter Maven and I had the privilege of participating in the “groundings” sessions that Vidya Kissoon and Sherlina Nageer conduct on the streets of Georgetown. We spoke to everyday people about their hopes for Guyana.

That is some powerful radical future-making right there.

Activists Sherlina Nageer, above handing a book to a school girl. And Vidya Kissoon, crouching over books they give away during their “Groundings” sessions, conversations with everyday people in Georgetown inspired by the late historian Walter Rodney.

I look forward to visiting my family here in Georgetown and journeying to the glorious, unspoiled Pomeroon River, and to speak with students, teachers, and families at my mother’s old Marlborough grade school this week about art. Like so many things my mother is right about she is right about this: She—and Guyana have never, ever been poor. Guyana is richer than anyone in Hollywood could ever conceive. Art is a means for each citizen to connect with their interior worlds, and to allow those riches to flower out. I believe the best is yet to come.

Tomorrow, Mashramani Day, my mother and I will wine down in the streets of Georgetown. We will carry a flask of El Dorado rum in hand, on the anniversary of the day on February 23, 1763, when Cuffy led the first major slave rebellion and ruled Berbice. We will share in the celebration of freedom. We will celebrate our strength, our resilience as a people. We have survived the forces that tried to erase us. We are still here!

We are so thrilled to be included. Thank you.