This July, I was part of a group academics, political advisors, playwrights and writers, international aid organizers, activists, professors and journalists who were invited to attend an “ideas festival” in the Aspen mountains, free of charge, as “scholars.” On the first day of the conference, we were invited to attend a session at which we discussed a reading: “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas” by Ursula K. Le Guin, a decorated American writer. The discussion of this story was a subtle way to explore the moral, ethical and philosophical dimensions attached to people of high education and privilege.

I offer the story and our discussion around it as a way to speak to many of the similar debates going on within IF about how we can best serve the public.

Le Guin’s short-story described a utopian city, full of wealth and abundance, where everyone was, intellectual, sophisticated and cosmopolitan. There were festivals of wine and food, and everyone got along wonderfully. About halfway through the story, you learn the secret of the city’s success: There was a child being kept in a dark, dirty closet. The child had matted-up hair, and if you got close enough you could hear the child pleading to be let out and promising to be “good.” All adults, upon coming of age, learned about the existence of this child. But they all knew that if anyone were to let the child out, all of their prosperity and happiness would vanish.

Omelas remained populated by people who accepted the child’s existence as the price to be paid for all the privileges they enjoyed. But the story ended with a few of the citizens who chose to silently walk away to places unknown. “But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas,” Le Guin wrote.

In our discussion in Aspen, responses to the story ran the gamut. Some were horrified at those who did not walk away. Others, especially those who did grassroots international aid work in some of the most wretched places of the earth, said there is another word for the existence of the child: “collateral damage.” My contribution to the discussion was to recall a class session I did with my Georgetown students this summer where we read and critiqued Pulitzer Prize-winning journalism. One Pulitzer Prize-winning article, “The Girl in the Window” featured the plight of a child in Florida was actually living this hell. The “feral child” was trapped for years in a closet, as the child’s mother neglected her and social workers failed to intervene.

So for me, not only was the existence of the child a matter of fact, I also had come to feel like I was beginning to taste a little bit of what Omelas might feel like since I joined IF. In IF-sponsored discussions, we have food and drink and discussion. We engage in civil deliberation with our fellow citizens around issues of importance to the whole country. I have described both IF and the Aspen Ideas Festival as kind of a “nerd heaven.” And to be engaged in this kind of life of the mind is an incredibly privileged thing to make a living doing this—to me.

One thing to remember, though, is that sitting around and talking about public policy is not everyone’s idea of a utopia. There has been some pushback against the idea that intellectual work is better than manual work by writers like Matthew B. Crawford, a University of Chicago-trained PhD who abandoned his career at a D.C. think tank and became a motorcycle mechanic. (See Crawford’s excellent piece in the New York Times magazine from 2009 in which he effectively challenges elites who say working with your hands is not creative, intellectual or valuable work.) Society has many lanes, each with their own rewards and limits. But when we at IF do our work with the assumption that everyone is thirsty for this kind of experience or considers it Omelas, it takes on an uncomfortable, missionary zeal.

I am living proof that the propensity or proclivity to want to experience IF discussions do not fall along lines of class or race. Upon embarking on my first project, my approach will be to invite a wide range of people to participate in IF discussions. Because I live in D.C. and because I have access to certain kind of social networks, there is a high probability that they will be younger and include more people of color. I believe that it makes for a richer discussion and a greater contrast in possibilities when more people from more walks of life are at the table. However, targeting a specific race or class on a particular topic makes assumptions about that group that are uncomfortable to me.

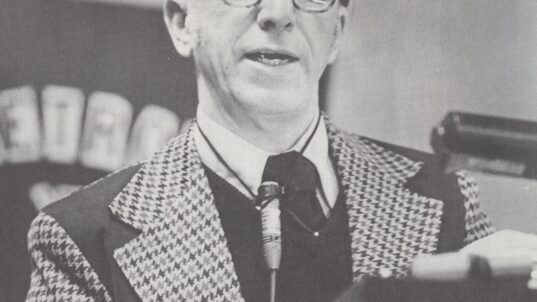

Unlike Le Guin’s work of fiction, there was no Faustian bargain that allows IF the privilege of being able to live in our own idea of Omelas: There was just the dogged determination of a man named Jay Stern. It is a quirk of history, West Virginia geography, energy policies, the legal system, and fate that all of us at IF are able to live on the fruits of the Stern family’s fortune. Upon being handed the baton with his family’s bank and coal land investments, Jay fought, scrapped and squeezed every last drop from those assets so that they may be used to fulfill his vision. He could have lived much fancier. He and Margaret could have adopted a brood of children to whom pass on their fortune. He could have bought jets and expensive clothes and spent his days traveling the world. He could have donated his fortunes to organizations engaged in actively breaking the child out of the proverbial closet.

Instead, though, he spent his remaining decades building his own kind of Omelas, brick-by-brick, in the form of the Interactivity Foundation. To the extent that his resources allowed, Jay wanted members of the public to not just be able to not just imagine it in a work of fiction, but to experience this kind of Omelas. That was his wish.

Back in Aspen, the session moderator concluded his presentation this way: “I know everyone in this room would tear down that door. That’s why you’re here.”

I’m still chewing over what that means. All I know is that none of the scholars walked away from Aspen. In fact, I’m hoping I get invited back next year.