PPE for Philly Sanitation Workers by Joe Piette on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA.

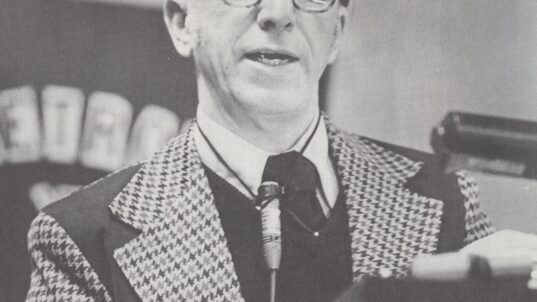

Among the chronic social conditions that have been brought into sharp relief during the COVID-19 pandemic is that of income inequality. The intersections of poverty, food insecurity, access to health care, and a range of other types of human needs have a bright light cast upon them in ways not seen since the Great Depression. There are increasing numbers of informal interactions at the grassroots level that seek to explore these issues and what can be done about them. I have been fortunate to be able to listen in on a number of online conversations organized by young activists trying to make sense of current social conditions. While they come to these discussions from somewhat different perspectives—Poor Peoples Campaign, Sunrise Movement, civil rights, and electoral reform groups—I have sensed some common themes emerging.

Inequality-averagehouseholdincome by Vince_Lamb on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA.

There seems to be a widening sense that society is “not working as promised”. While few younger activists use the descriptive term “social compact,” that term sums up many of their concerns. The common questions often revolve around “what is the moral society,” “what do we owe each other,” and “what human needs are human rights.” Many participants in these current online discussions already have social justice perspectives that fit handily with these challenging times. Some, however, find the times eye-opening and have their “work within the system” outlooks replaced by concepts of “systems change.”

It should come as no surprise that recent events provide a powerful context to many of these discussions. I heard no participants in any of these online discussions who thought it was possible to discuss income inequality and what society could/should do about it without addressing racism in the United States. For many, the pandemic crisis also exposes fault lines between the working poor and those with ability to work from home or otherwise protect themselves from COVID-19 exposure. For many in the service and health care sectors, the refrain has become “we are essential, but expendable.”

City of Santa Clarita by National Nurses Day Event 2 on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA.

It’s possible, I think, to group many of these concerns into some clusters that serve as grist for further citizen discussions of concerns our society should take a fresh look at. My own sense is that they mainly express themes revolving around economic benefits, health care systems and public health, sustainability, and political participation. I also found that these discussions grappled with specifics within these broad categories.

In terms of economic assistance, there was much emphasis on immediate relief in the form of cash assistance. For most, a national basic income is a long overdue no-brainer. There was also a desire to see more citizen involvement in economic development. This desire is entirely consistent with what colleague Natalie Hopkinson and I found in our project On Giving: the Future of Philanthropy. The common refrain being, “don’t help us without involving us.” In concrete terms, this comes up as a belief that the poor and marginalized deserve representation on the governmental and non-profit boards that impact their lives.

Occupy Chicago Protest by Ken Fager on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA.

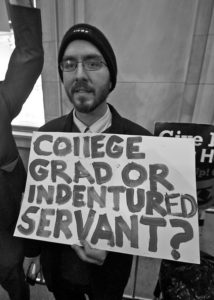

Issues of “debt” are also pressing in many minds. Many individuals have a sense of drowning under financial obligations that they now have difficulty meeting. These discussions shared a belief that the concepts of “forbearance and forgiveness” are essential during a time when incomes are reduced or eliminated. Abolition of student debt was the most commonly cited objective. Close behind was the desire to see evictions and foreclosures suspended until we see a more robust economic recovery.

It seems quite natural that health care issues would come up in discussions centered on income inequality. It certainly factored in matters related to COVID-19 exposure and treatment. At the same time, those I was listening to had a solid appreciation for the glaring deficits of our public health systems in terms of prevention and supportive services like nutrition and physical activity. The enormous sums allocated for “bailouts” also had them scratching their heads about the so-called impracticality of Medicare-for-all. In their minds, health care is a human right.

CCC Logo by George Lane on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA.

On sustainability issues, there was an interesting engagement on proposals large and small, from Green New Deal and Trillion Tree Project to replacement of the consumer society with the ethic of “living lightly on the land.” Most of them thought that steps toward energy efficiency, non-carbon alternative energies, recommitment to clean air and water, and rebuilding our aging infrastructure were essential parts of both a responsible vision of the future and a path toward job creation in a time of economic recovery. They also weren’t afraid to look backward—the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps was dusted off for further inspection.

In all but one of these discussions that I followed, the eventual destination turned out to be the governance system itself. At first glance, it sounded like a focus on “more”—more voting, more public conversation, and more participation. The mobilization of the voters for the November 2020 election was foremost in their minds, with items like countering voter-suppression, mail balloting, and election integrity part of that picture. But they also saw the need for long-term democratic renewal. Most saw themselves as part of a reinvigorated civil society movement that could involve low -income people and amplify their voices. It probably will come as no surprise that their desire to see more people voting was matched by their desire to see more people in the streets demanding justice.

So yes, today’s young, socially conscious adults are confronted with an array of difficult circumstances. Yet, they are hopeful that there are answers to the problems that confront us. And they see themselves as part of those answers.