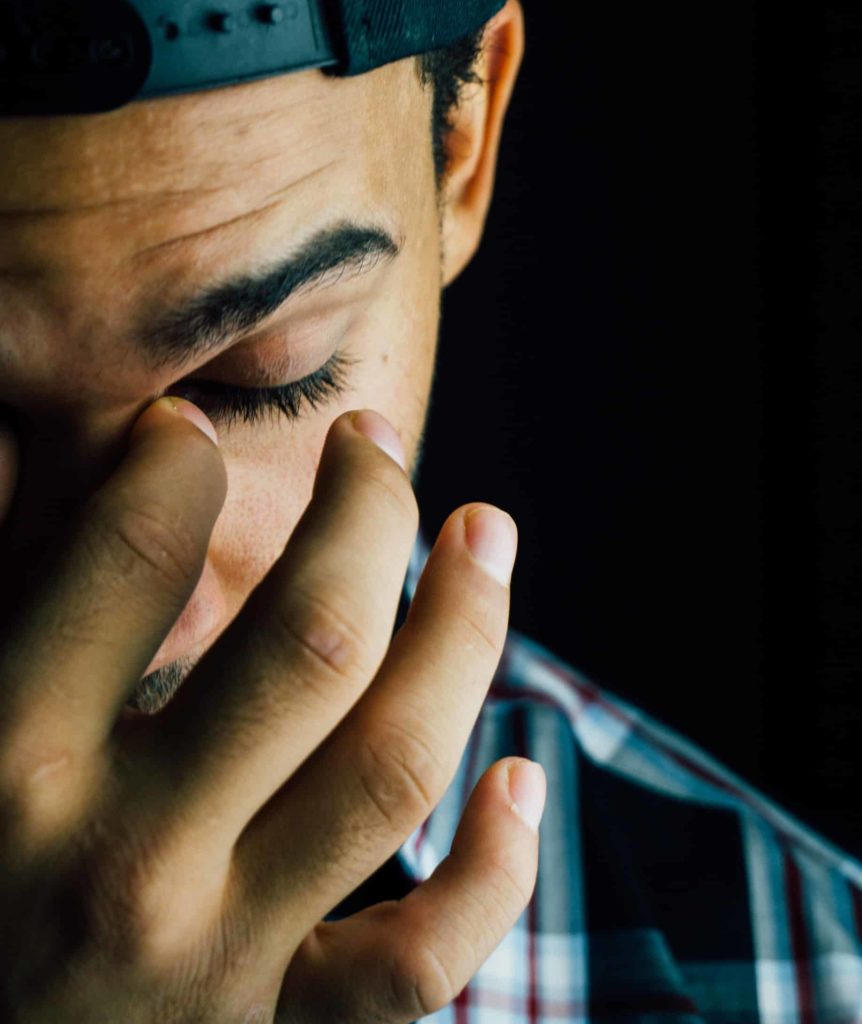

Man Pinching Nose via Pixabay

How can we help students to be sensitive to contrasting perspectives?

Dr. Jerry Watson was disturbed when one of his students walked out of his Moral Issues class. It was during the class discussions so Watson left his seat to go after the student. The student, Mike, was standing by the elevator with tears in his eyes. He was obviously troubled. Watson asked Mike to meet him at his office after class.

When class was over Dr. Watson asked Mike what was wrong. “Our group was discussing reproductive freedom. Everyone seemed so one-sided about the subject. They agreed that a woman should have control over her body. Well, my girlfriend just terminated her pregnancy without talking to me about it. I had no say in the matter. I tried to bring up the rights of men and consulting with partners when ending a pregnancy, but my comments were treated with disdain. I didn’t want to discuss my own personal situation, and I was just too torn up to continue the discussion.”

As Watson thought about Mike’s case, he felt he needed to do something about managing the personal sensitivity of students during in class discussions. Trigger warnings had become a popular way to deal with sensitive material, but Watson didn’t feel like they would work in his class. The discussions were just too free flowing. He couldn’t imagine how to prepare a trigger warning in advance of a discussion where he didn’t know where the discussion might go. More generic warnings just didn’t seem that they would be effective.

What Watson decided was to create a series of personal descriptions of issues that previous students had faced. Rather than trigger warnings, he wanted students to be conscious of how their comments might affect those past classmates if they were in the discussions today. What he hoped to do was make students sensitive to how their comments might be viewed by others. Each student was asked to “own” one legacy perspective and, when discussions became insensitive to the legacy, the student needed to point that out. Some examples that Watson drew from his past years of teaching:

- A Latino student whose cousin and best friend were killed in gang violence. He was “saved” by a white police officer who gave him the money to leave town.

- A student whose mother was in jail for DUI vehicular homicide.

- A student whose boyfriend committed suicide when she broke up with him.

- A student and single mom whose parents secured a court order to take custody of her child.

The result of incorporating the legacy descriptions into the discussions was remarkable. The discussions became more civil and tolerant of views beyond those of the group. But even more importantly, the discussions became deeper because students became more aware of how others might approach the discussion topics.

At the end of the semester, Watson asked each student to prepare a legacy description that was personal to them. That way he would have a continuing repertoire of situations students faced that he could use in subsequent semesters. What approaches do you take to foster exploratory discussions of sensitive topics? Share your ideas and responses via Twitter @IFTalks or FaceBook @whatIFdiscussions.

* * *

“Peaceful people do not just happen.” – Elizabeth Kübler-Ross (psychiatrist known for her work on the five stages of grief)

This post is part of our “Think About” education series. These posts are based on composites of real-world experiences, with some details changed for the sake of anonymity. New posts appear Wednesday afternoons.