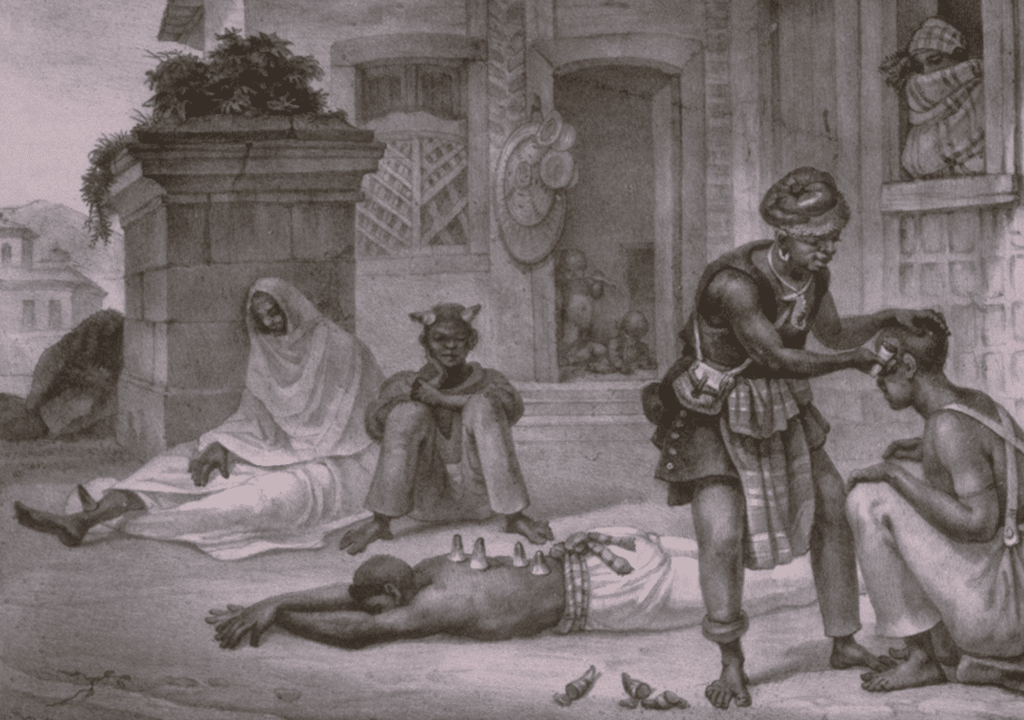

Jean Baptiste Debret/slaveryimages.org/CC BY-NC 4.0

Sometime in the late 1600s or early 1700s, an enslaved man was brought to America from a region in west Africa now called Ghana. He was presented to Cotton Mather, a Puritan minister and thought leader in colonial Massachusetts, as a gift from his congregation. Mather named him “Onesimus,” after an enslaved person mentioned in the Bible.

At the time, smallpox outbreaks were common in the colonies. In a 1716 letter, Mather writes how he had asked Onesimus if he ever had smallpox:

“…he answered, both, Yes, and No; and then told me, that he had undergone an Operation, which had given him something of the Small-Pox, and would forever preserve him from it, adding that it was often used among the Guramantese, & whoever had the Courage to use it, was forever free from the Fear of the Contagion. He described the Operation to me, and showed me in his Arm the Scar.”

What Onesimus described as an “Operation” is a procedure now called variolation, where fluid from a smallpox blister would be introduced into a small cut on a healthy person.

Mather subsequently advocated for Onesimus’ procedure, especially during the smallpox outbreak of 1721. By and large, the elite of Boston were outraged at the idea of introducing disease in order to combat a disease. They also couldn’t believe that an enslaved person had the knowledge to prevent the spread of a deadly disease. However, Zabdiel Boylston, a local physician, was a believer who went on to successfully inoculate 287 patients, who had a death rate six times lower than those without the procedure. Dr. Boylston was given credit for pioneering the use of inoculation procedures to prevent the spread of viruses. Two hundred years later, Onesimus was finally given credit and listed as number 52 out of 100 of the Best Bostonians of All Time.

In our society today, we tend to equate formal education as a necessary factor in a person’s knowledgeability. In reality, our knowledge comes from many sources. In Onesimus’ case, his knowledge of the prevention of smallpox came from experience. We often disregard knowledge that doesn’t have the imprint of formal education. Additionally, we’re often quick to dismiss sources of knowledge that come from other cultures or from those who are socially marginalized within our own culture.

When we think of how we develop people to be contributors to society, we need to think more holistically. How can we help them gain experience? What does it take to inspire people to expand their insights through curiosity and perceptiveness? How do we make sure we are open to the insights and experiences of those we tend to overlook or marginalize?

Just imagine a society where one’s personal background and formal education are not determinative of the contributions one can make to society. Would a breakthrough idea from an inner-city youth or an undocumented migrant be any better received today than in Onesimus’ time? Just imagine how we might change the way we think about human development based upon the various kinds of knowledge that are needed. Just imagine what we might do to encourage openness to learning from those whose life experiences are so different from our own. How might we make room to learn from the experiential knowledge of people like Onesimus in our own time?

* * *

“Information is not knowledge. The only source of knowledge is experience. You need experience to gain wisdom.” –Albert Einstein

This is part of our “Just Imagine” series of occasional posts, inviting you to join us in imagining positive possibilities for a citizen-centered democracy.