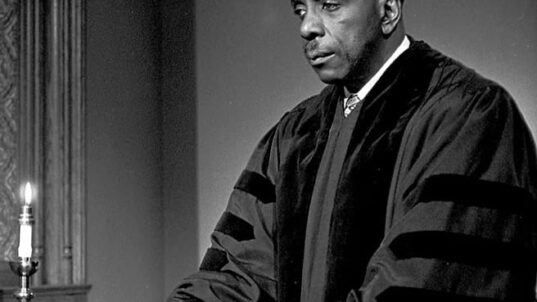

Kuntrell Jackson via www.eji.org

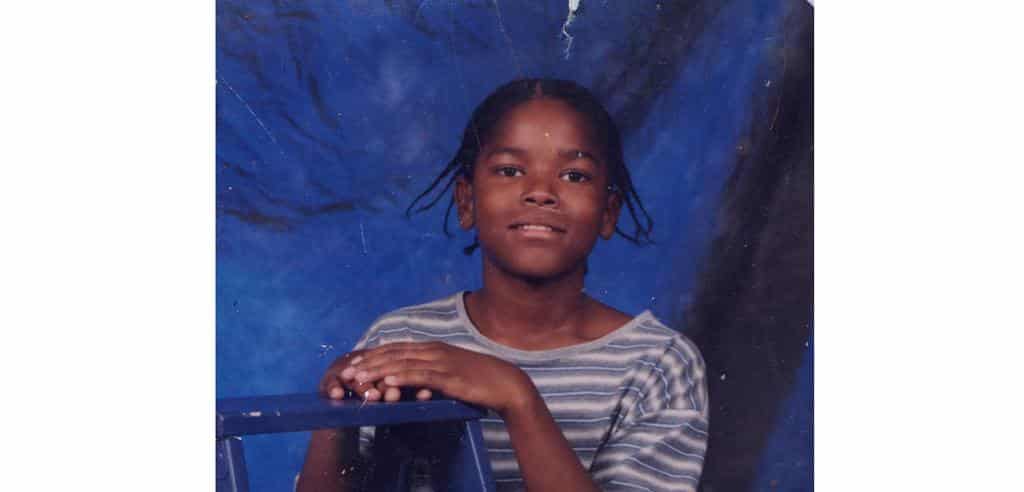

In 1999, Kuntrell Jackson, his cousin Travis Booker, and a friend named Derrick Xavier Shields were wandering around the housing project in Blytheville, Arkansas. The projects were a violent place to grow up. One of the boys suggested they rob a nearby video store. While the two other boys went inside, Kuntrell remained outside as a lookout. He had just recently turned 14. The other boys were of a similar age.

After a few minutes, Kuntrell grew nervous and went to check what was going on inside. Shortly after he entered, Derrick shot and killed the store clerk. The boys fled without taking any money.

All three were eventually tracked down and arrested. Despite the fact that he was only 14 years-old, Kuntrell was charged and tried as an adult. He was found guilty of capital murder and armed robbery, even though he was not the shooter and had not stolen anything. He was sentenced to mandatory life in prison without the possibility of parole. He would serve his sentence with the adult population of a maximum-security prison. He was sentenced to die in prison.

Was justice done? Does a life sentence given to a minor constitute cruel and unusual punishment as envisioned in the 8th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution? At what age, and under what circumstances, should a minor have the legal and moral accountability of an adult?

In 2012, the US Supreme Court decided that it was unconstitutional for minors to be sentenced to life imprisonment without the possibility of parole. In Kuntrell’s resentencing hearing in Arkansas, the court was allowed to consider his age and life conditions at the time of the crime. He was sentenced to twenty years and released in 2017 on parole after serving sixteen and a half years.

This case and many others raise questions about what we mean by the term “justice.” Is justice meant to be a retribution for a crime committed no matter the circumstances of the crime or the condition of the person committing the crime? Is justice meant to be proportional–and, if so, proportional to what? What benefits do we gain by having uniformity in our system—with things like mandatory minimum sentences? What leeway should there be for consideration of mitigating factors in such decisions? How might justice be applied fairly when the wrongs are committed by more than one person?

Just imagine how we might reconceive the concept of justice as our society has evolved. Just imagine how justice might be administered based upon human values and separated from political considerations. What if those values lead us to repair the conditions that are more likely to lead to criminality? What could we do to restore the health of society in order to prevent wrongdoing—in addition to having a restorative mission for those committing wrongs?

Today Kuntrell is an activist and author who works on criminal justice reform as well as on addressing the issues of neglect, violence, and poverty that lead to mass incarceration. You can learn more about his work here.

* * *

“Justice is conscience, not a personal conscience but a conscience of the whole of humanity.” – Alexander Solzhenitsyn (Nobel Prize winner for literature)

This is part of our “Just Imagine” series of occasional posts, inviting you to join us in imagining positive possibilities for a citizen-centered democracy.