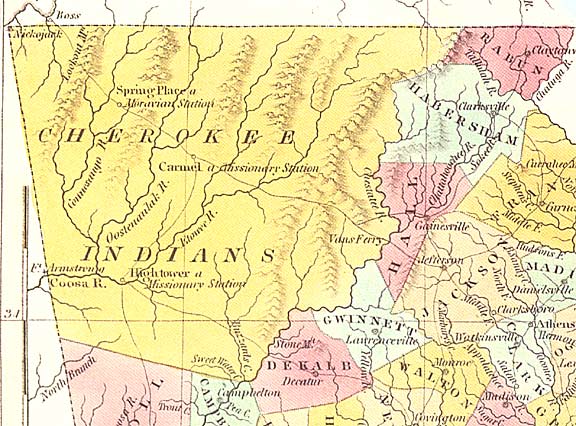

Cherokee Nation Map 1830, public domain via wikimedia

The founding fathers were concerned to make sure that the government they were creating should not have the power to take people’s property for public use without the owner’s permission. In the Fifth Amendment, the so-called takings clause was added, stating that property could only be taken for public use and the property owners must be fairly compensated. States followed suit with similar provisions in their constitutions.

Over time, the process called eminent domain has been used for vital public uses such as highways, public building projects, parks, etc. But the concept of eminent domain has been expanded from public use, or things that are directly used by the public, to public purposes, or things that are seen as in the public interest, even if they are not directly used by the public. The original intent of the Fifth Amendment has been left behind.

Through decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court, public purpose has increasingly been linked to economic value. If the new use of the property can be justified as one benefitting the public via greater economic returns, then eminent domain applies. This new interpretation has proven to have devastating consequences on those of lower socio-economic status. It’s hard to believe that this was the original intent of the founding fathers.

While the founding fathers had seemingly spelled out the dangers of governmental entities taking private property, the enforcement of the takings clause in the Fifth Amendment has been lax by all three branches of government. One of the most blatant examples is the confiscation of the homeland of Native Americans.

President Thomas Jefferson started the process of strategizing for the removal of Native Americans from their homelands east of the Mississippi. Then in 1828, the State of Georgia passed laws that effectively removed the Cherokee Nation from their homeland in the state. When the Cherokee Nation fought their removal in court, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to rule on the case, holding that the Cherokee Nation lacked standing. Chief Justice Marshall, another founding father, wrote this shameless justification. Opinions of other justices were equally shameful, calling the Cherokees wandering hordes. The Fifth Amendment never entered their decision making. So much for original intent.

A year later, the Supreme Court, in an apparent act of conscience, reversed their decision. President Andrew Jackson, however, ignored the Supreme Court and ordered the U.S. military to begin the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation in what we now call The Trail of Tears. Jackson suffered no negative consequences for ignoring a Supreme Court decision.

Just imagine the precedent set by the removal of the Cherokee Nation on subsequent developments throughout U.S. history. While the concept of “original intent” has become popular in viewing of cases brought to the U.S. Supreme Court, this concept continues to be ignored when a powerful interest has a desire of taking the property from a less powerful interest. Where else have we lost a sense for the original intent behind the key features of our democracy?

* * *

“…nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”– the “takings clause” of the Fifth Amendment

This is part of our “Just Imagine” series of occasional posts, inviting you to join us in imagining positive possibilities for a citizen-centered democracy.