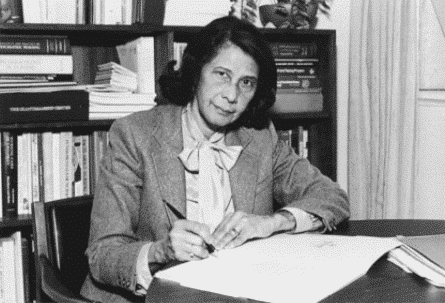

Callie House, public domain image

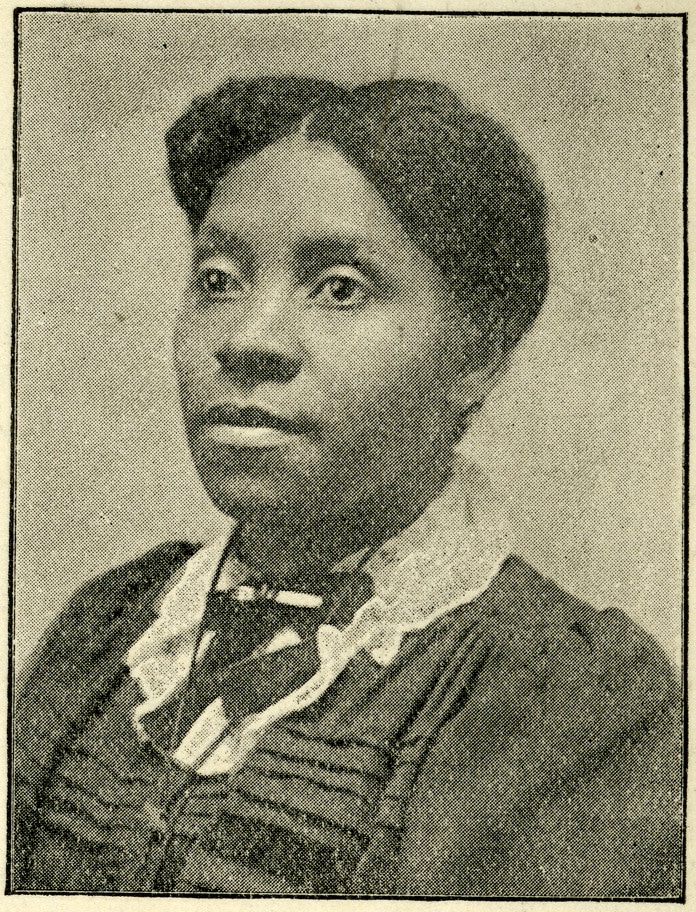

Callie House was born in 1861 as an enslaved person in Tennessee. She was freed by the Emancipation Proclamation. She married at age 22 and went on to have six children. Her husband died early, and she had to take work as a washerwoman to support her family.

At the conclusion of the Civil War, formerly enslaved people struggled greatly to earn a living. Some governmental efforts were made to give them a means of independent living, along the lines of US General Sherman’s order of “40 acres and a mule.” But these efforts were stymied and soon reversed as white supremacy gained the upper hand against the Reconstruction vision of a more free and equal society. As a result, many of those who were formerly enslaved now found themselves forced into situations that were not a far cry from their former status.

The Freedman’s Bureau had been established by Congress in 1865 to aid the transition from slavery to freedom. But President Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, vetoed the renewal of the Freedman’s Bureau and failed to enforce other efforts to support the formerly enslaved. Other efforts during his administration to improve the living standards of the formerly enslaved were either unenforced or otherwise fell short.

Some of those formerly enslaved, like Callie House and the Reverend Isaiah Dickerson, decided to take action. Using the model of the pension benefits received by union soldiers, they established the National Ex-Slave Mutual Relief, Bounty and Pension Association (MRB&PA) to advocate for economic reparations for former slaves. Callie House became a leader of the organization in advocating for pension benefits.

As the MRB&PA gained membership in the late 1890s, it faced determined opposition from three federal agencies: the Bureau of Pension, the Post Office Department, and the Department of Justice. The Post Office accused MRB&PA of using the mail to defraud formerly enslaved people. There was no evidence to support these charges. Still, the Post Office worked to block the movement by intercepting its mail, and marking the mail as “fraudulent” or simply blocking its delivery.

Under Callie’s leadership, the MRB&PA also sought relief through the courts, filing a class-action lawsuit in 1915 demanding reparations based upon cotton taxes collected from 1862-1868. On appeal, this class-action lawsuit was rejected by the Supreme Court in one of a series of the Court’s reactionary decisions that helped to end any progress made by Reconstruction.

In 1916, the Post Office, continuing its effort to suppress the MRB&PA, secured a fraud indictment against Callie. In short, the prosecution’s case was that she should have known that the government would never do the right thing by providing reparations, so her efforts had to be deemed fraudulent. Callie was convicted by an all-white, all-male jury and given a one-year sentence.

When Callie got out of prison in 1917, she returned to working as a laundress to support herself. She died in 1928 and was buried in an unmarked grave. While she was unsuccessful in getting reparations for former slaves during her lifetime, the effort continues. With the passage of time, this effort to seek economic reparations has been further complicated by the growing challenge of identifying ancestors of former slaves. In the meantime, our society has added further economic injuries to Black Americans, with policies like redlining explicitly excluding African Americans from federally insured mortgages.

Just imagine how different our society would be if our national government had made an honest effort at reparations right after the Civil War. Imagine if we had committed not only to full civil, social, and political equality at that time—but had also committed to closing the racial wealth gap caused by the enslavement of Black people as property. As it stands, the inequalities we have built into our systems operate like compounding interest to further expand the racial wealth gap over generations. Will Callie’s efforts ever be rewarded? When will we decide it’s time to meet this demand for justice?

* * *

“If I take the wages of everyone here, individually it means nothing, but collectively all of the earning power or wages that you earned in one week would make me wealthy. And if I could collect it for a year, I’d be rich beyond dreams. Now, when you see this, and then you stop and consider the wages that were kept back from millions of Black people, not for one year but for 310 years, you’ll see how this country got so rich so fast. And what made the economy as strong as it is today. And all that slave labor that was amassed in unpaid wages, is due someone today. And you’re not giving us anything when we say that it’s time to collect.”—Malcolm X

This is part of our “Just Imagine” series of occasional posts, inviting you to join us in imagining positive possibilities for a citizen-centered democracy.