Arearea, by Paul Gauguin – via The Yorck Project (2002)

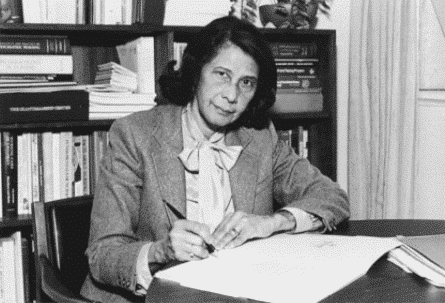

Professor Clorinda Delgado couldn’t believe what she was overhearing from the discussion groups she had set up in class. She had asked her class to discuss their views of Paul Gauguin’s paintings from Tahiti. The discussion question was this: “How would you assess whether Gauguin’s paintings of the natives of Tahiti should be considered exploitative, according to current cultural standards?”

Delgado thought this was a question worthy of discussion but what she was hearing was this:

- “This is absurd. You know what she wants us to conclude.”

- “Why are we bothering with a discussion when we will be criticized if we come to a conclusion she doesn’t like?”

- “Does she really think that having us discuss this will somehow make us more accepting of her propaganda?”

Delgado was shocked. She genuinely wanted to hear what her students had to say. She wasn’t trying to force any conclusion. In fact, she didn’t really know how she felt about the question.

The experience that Delgado had is fairly common when groups are formed to discuss an issue. There is a natural skepticism about motives behind the discussion. Often there are those in the group who believe that the purpose of the group is to reinforce what the instructor (or discussion leader) wants them to accept. Unfortunately, that skepticism may often be well founded.

When Delgado heard the comments, she stopped the class and said: “Your thoughts will be very helpful to me. I’ve taught Gauguin for years and still don’t know what I think about whether his paintings were exploitative.” While it’s likely that discussion participants are likely to be skeptical about the intent of the discussion, there needs to be an upfront assurance of the intent. The more personal the assurance, the better.

Should skepticism remain, the facilitator may need to stand firm by asking the group to say what they think. Then make sure that the group’s ideas are fully developed by asking: “How might others view our ideas?”

Typically, the skepticism will be overcome on an individual basis. Early believers will gradually help others become believers.

It’s also helpful to do a preliminary review of the ideas with the instructor or leader of the group at some mid-point in the discussion. These reviews can also overcome skepticism if the instructor asks questions that are looking for insight into the thinking of the group. The review can also show how the group is developing a range of contrasting ideas. This helps to encourage the understanding that the group is not being directed toward a preferred or correct answer.

It is inevitable that there will be doubters in any discussion and there needs to be a strategy for dealing with these doubters at the onset of any discussion.

* * *

“The improver of natural knowledge absolutely refuses to acknowledge authority, as such. For him, skepticism is the highest of duties; blind faith the one unpardonable sin.” – Thomas Huxley (Biologist, anthropologist, and contemporary supporter of Darwin)

This post is part of our “Think About” education series. These posts are based on composites of real-world experiences, with some details changed for the sake of anonymity. New posts appear on Wednesdays.